Scientism is used as a pejorative. I could argue it is a reaction of philosophy to science, in a similar way that Luddites react to technology. Generally, scientism is seen as a use of science that is in some way inapplicable to a phenomenon or circumstance.

Science

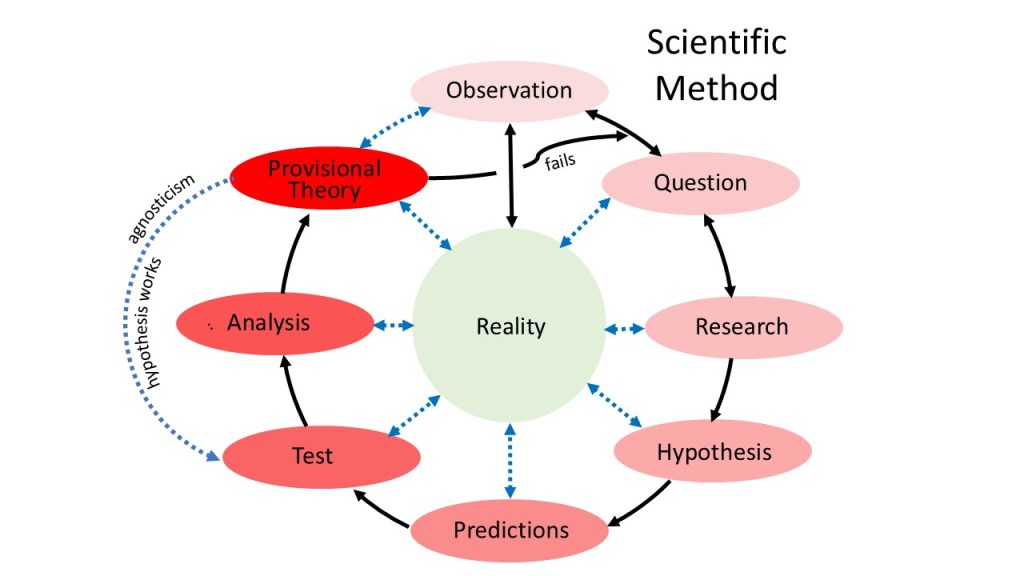

But first, what is science? Well, it is a method for answering questions and providing descriptions of phenomena that we find in the real world. These descriptions are more than our everyday “descriptions”. These descriptions tend to have predictors built into them. Here is a schematic for the scientific method:

There is some philosophical debate as to whether these descriptions require an ability to predict, ie, be testable or even falsifiable. A lot of physics is on the ‘bleeding’ edge of our abilities. In effect, a lot of our hypotheses are, in practice, untestable.

So the scientific method in words:

Observation: We start by observing some aspect of reality – our world. I can’t see a reason to somehow limit it to particular disciplines. Whether it be physics, psychology, or even our perceptions.

Question: We ask questions. What might be the causes of what we are observing? Are there any similar phenomena? Has anyone else seen this or something similar? Is there any particular type of observation we don’t want to question?

Research: By asking questions, we collect additional information.

Hypothesis: This allows us to speculate about a mechanism or perhaps a rule. Any reason not to form speculations/hypotheses about religion, gods, or consciousness?

Predict: Often, our speculations allow us to make predictions. Even if it is that our hypothesis can be repeated, or even that we might see some other phenomena that have not yet been observed.

Test: We go into the laboratory and experiment, or out into the real world and look for more data, eg, the collider or paleontology, looking for fossils or looking at societal behaviours.

Analysis: Do our observations satisfy our predictions? Or do we just ignore the ‘tests’ and data from the field, and let our intuitions or even speculations run riot? Note that the analysis is not done by just the authors, but by a community of publishers, peer reviewers, and fellow scientists. Not all of whom may be on board.

Provisional Theory: After decades of reproducibility and corroboration, we get to “theory”. But even then, the theory is a piñata. Take Newtonian mechanics. It stood the test of time for two and a half centuries. Today, we understand it is incomplete if not wrong, but our skyscrapers stand, bridges span, cars drive, and chemical plants produce, based largely on Newtonian mechanics.

Note that the scientific method is agnostic, even if scientists and advocates of scientism might not be. Ideally, the advocates of scientism might be a little agnostic in their claims.

Scientism

It is difficult to understand the motivation of those who object to scientism. If the scientific method works (or can be made to work) for helping understand the vagaries of the human condition, so much to the good.

From my perspective, we can divide scientism into two broad camps: weak and strong (soft and hard). Advocates of weak scientism might suggest that science is the best tool to gain understanding and perhaps knowledge. (What knowledge might be is for another thread, especially from an agnostic point of view.) Advocates of strong scientism might argue that it is the only way to gain knowledge. They would argue that if something can’t be verified, it is not knowledge; and verifying is part of the scientific framework.

Typical adjectives used by polemicists of scientism are arrogant, greedy, overreaching, reductive, dismissive, and perhaps amoral. Below are a few of the criticisms levelled at scientism. Having said that, we need to be careful not to confound advocates of scientism with the application of the scientific method to most, if not all, aspects of our lives and society in general.

Arrogance

Science is the best—or the only—reliable way to gain knowledge about reality.

I think that the split between science and philosophy is daft. Indeed, I would argue that science is probably the most useful and enduring product of philosophical thought. Here, one might argue logic, formal and informal, and mathematics may also be contenders for the honour.

Philosophy, having brought science to life, why would it not welcome its use when evaluating human activity? It could be argued that philosophy is part of the scientific method wheel.

So, if some philosopher claims other methods are reliable, then if this can be tested, I am all for it. Now, can religion tell us about reality? The Buddhist tradition ends up in a very different place from the Christian tradition. How can we tell which corresponds to reality more accurately? Now, of course, some may hold some hidden knowledge, but how do we tell which is more accurate, and if it works, and in what situations? To do this successfully, the religious person has to jump onto the scientific method wheel at some point. We might not call it that, but that is what we are doing. Christians might in some sense argue that the New Testament is an update on the Old. Hadiths and Muslim apologists provide clarifications of the ambiguities in the Qur’an.

Similarly, all the different schools of philosophy are trying to describe reality more accurately. They, too, are grinding away on the wheel of the scientific method. Or, having found some alleged knowledge, is it just asserted almost a priori?

Similarly, people use intuition all the time. It is an evolutionary capability that is often very useful. The classic example is Kekulé’s daydream of snakes biting their tails. But Kekulé was well on the scientific method wheel at the time, and he got back on it after the daydream.

Overreach/Greedy

Scientific methods can (or eventually will) be applied to all meaningful questions, including those traditionally reserved for the humanities or religion. Everything that exists is ultimately explainable in physical terms.

So, if we were to ask, does intercessory prayer work? How do we go about assessing this question? Well, one way is to ask a whole bunch of people and record their examples of where it worked or not. We would get a whole bunch of anecdotal answers, and we wouldn’t know what the data actually meant. Or we could study the effect of intercessory prayer on a particular type of recovery from a heart operation. In 2006, 1800 heart patients were part of a study; one-third were prayed for by strangers for speedy recovery, and were not told. One-third were not prayed for. There was no statistical difference between these two groups. Well, it is not surprising, these were strangers doing the praying. And the last third was also prayed for by strangers, but they were told they were being prayed for. Surprisingly, as a group, they did worse. So, if you ever want to pray for me, please don’t tell me. I don’t want to succumb to the nocebo effect. Of course, apologists will claim God can’t be tested.

So yes, things can be difficult to measure. Does socialism work; in what sense did socialism fail in the Soviet Union; is the socialist amalgam working in China? The historian will work through these questions, they will look at what they know, develop a hypothesis, gather evidence, and see if it fits the evidence. Even the most perfunctory journalism will verify its sources, it plays on a small part of the scientific method wheel. Investigative journalism will go all the way round.

I guess some polemicists of scientism don’t want these things to be measured and confirmed. The fact that the more nebulous questions are difficult to measure or currently impossible to measure is neither here nor there. Understanding how a rainbow works makes it no less beautiful. And understanding the brain states that classify beauty is no less wondrous.

Not competent

Scientism tends to underestimate the complexity of some questions, especially in human domains.

Well, my scientism does not underestimate the complexity of some questions. Again, it is people, not science, that are doing the alleged underestimating. But in my worldview, it makes sense that each domain, physics, chemistry, biology, sociology, history, and the rest, is coherent with the domains around it. This, to all intents and purposes, is infinitely complex. This is why we break it up into the various disciplines and then try and stitch it back together again.

I am reminded of this fifteen-year-old program where researchers could reconstitute (poorly) what people were seeing from fMRI brain scans. Just bear in mind that the fMRI is measuring blood flow to various parts of the brain. This is like determining the surface of an egg with a hammer. Imagine what we could do in a hundred years.

Often, we get questions like: Can science prove that suffering is bad? Or that genocide is wrong? Or that a painting is beautiful?” Would a Buddhist say, avoiding suffering is bad?

Then we have arguments such as Stephen Gould’s Non-overlapping Magisteria (NOMA). It is claimed that science and religion are separate domains and do not relate to the same issues. Of course, we have criticism from both sides of the aisle here. Francis Collins thinks there isn’t an extensive no-man’s land between them. Though Collins recognizes that ‘values’ are off limits for science. Not surprisingly, Sam Harris and Richard Dawkins disagree. Dawkins notes that if divine intervention is a thing, it would be worthy of scientific study.

Reductionism

Complex phenomena can and should be explained in terms of their simplest parts.

There might be the odd, and here I stress odd, advocate of scientism that suggests we explain complexity using the simplest parts. I find this position strange, in that our collective understanding of the simplest parts is murky, despite the phenomenal predictive precision of the parts. Doing a quick search, people who are accused. I would recommend, Simple as possible, but no simpler. But this does bring into question what we mean by “simple”. A myriad of tiny simples all interacting, or a few biggish simple black boxes that are opaque to the machinations.

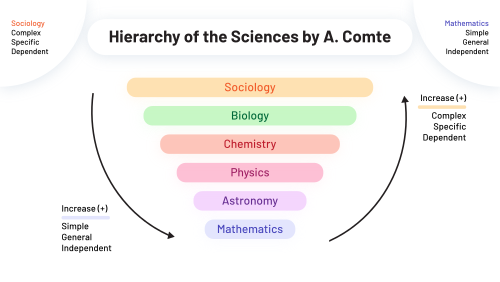

Now, I am not a fan of Auguste Comte, but he is considered an advocate of proto-scientism. He proposed a hierarchy of sciences. It went like this:

As it happens, I think Comte was not a good promoter of scientism. For example, he “condemned all talk of atoms, the innards of stars, and other unobservables.”1 Regardless, to me, it is logical that we should be able to slip coherently between the different disciplines cited without having to shift our worldviews.

Trying to solve society’s problems at the quantum level is obviously nonsense. But if the quantum realm is random, then I think it is reasonable to think that some elements of that randomness will filter up to larger structures, including societies. Similarly, if physics is deterministic, then we can expect chemistry, biology, and society to be deterministic even if it cloaked chaotically to some degree. This does not mean we should not use the appropriate level of model for our study, but we might acknowledge the uncertainty in the outcome and keep a close eye on the scientific method.

Dismissive

Philosophy, religion, and art are seen as obsolete, speculative, or meaningless unless they align with scientific findings. Non-scientific methods (eg, intuition, religion, philosophy, art) are discounted.

Arguments may go along the line that scientism does not recognize the contributions of religions made to science. The contributions include preserving knowledge, creating institutions of learning, prompting and motivating new inquiry, guiding ethical concerns, and perhaps laughably, demarcating a boundary between science and religion. There may be an element of truth in this. Scientists aren’t known for their book-burning fetish. That is more politics and religion. Galileo and Scopes got to see the light of day, but Bruno was not so lucky. Science at early religious universities was to understand and glorify God’s creation

What does ‘The Scream‘ tell us about reality? It certainly invokes an emotion of anxiety in me, but is it really providing knowledge? When I stub my toe, does it give me knowledge beyond stubbing toes can cause pain; certain images can cause anxiety? It can be claimed that the painting teaches us about 19th-century European anxieties: urbanization, alienation, and mental distress. Munch’s notes in his diary were more illuminating, I thought. This painting resonates with nearly everyone. Why? I feel a scientific study coming on. Some may argue for some kind of symbolic knowledge. Here I am reminded of Carl Jung’s archetypes. Jung drove himself almost to the point of psychosis to develop this schema. Or is the alleged knowledge we get simply a projection of our past interactions with the world?

Amoral

Societal progress is best guided by science.

Critics here are asking, can science provide society with its values, morality, and ethics? Now, people like Sam Harris would argue yes, as he does in his book The Moral Landscape. I happen to disagree with Harris here. I argue against morality and for amorality here. To me, the concerns here are begging the question that morality and similar exist. “Science can be used to justify harmful ideologies”. True, but then religions and politics are not exactly infallible. Philosophers don’t escape completely, take Ayn Rand’s Objectivism, where rational self-interest is the highest moral good. Yes, human beings can have an infinite ability to screw-up. So, science won’t protect us here.

For example, what should we do about climate change? Burn baby burn is one political, come philosophical view. Some theologians, certainly not all, think God gave us this planet, and we can do as we wish.

False Creditability

Using the prestige of science to lend credibility to fields or claims that only mimic scientific form.

Science has prestige because it works. Yes, science has problems imposed on it that result in this observed mimicry. The pressure to publish in academic circles is tremendous. Consequently, not all science is of the highest calibre. This is particularly true of the humanities. Of particular concern would be psychology, where there appear to be replicability issues. Of course, as a discipline, remedies are being put in place. This is not to say psychology is in some way flawed. It is a difficult and very young discipline. And it is not as though other fields do not have their problems with replicability; medicine, neuroscience, and political science are examples. Interestingly, sciences like political science and economics have the potential to feed back and affect the behaviours that are being studied.

If we contrast this to philosophical ‘gender studies’, a qualitative discussion of gender issues, then the social sciences are way ahead of the game.

Hard Scientism

I have some sympathy for the hard scientist, but I would disagree with the idea that science is the only way to get to knowledge. Having said that, any potential insight we might get from religion, intuition, art, literature, or indeed just thinking about things, unless we reach out into the world and in some way verify our insight, it is not knowledge, at least not in my book.

If done properly, science is hard work and can be costly. Intuition is a handy shortcut, but its products must not become doctrine.

Conclusion

In writing this piece, the thought crossed my mind, why would any polemicist of scientism object to a method of trying to access reality accurately? If the scientism apologist believes they are right, let them go for it. Similarly, for hard scientism apologists, let philosophers pontificate, and see what they find. So long as theologians and the like don’t propagate falsehoods, it’s not a problem.

When researching this blog, I frequently came across the claim that science gives us explanations but not understanding. I find this strange.

1 Mario Bunge, In Defence of Scientism. If a philosopher defends scientism, and if philosophy adds nothing of value, is it worth reading?